Introduction

In the realm of decision making, the Middle Ground Fallacy is a mental model that highlights the tendency to believe that the truth or the best solution lies somewhere in the middle of two extremes. It is the mistaken belief that finding a compromise between two opposing viewpoints automatically leads to the most rational or optimal decision. In this blog post, we will explore the Middle Ground Fallacy, its relevance in decision making, its anchoring in human psychology, and its prevalence in our day-to-day lives.

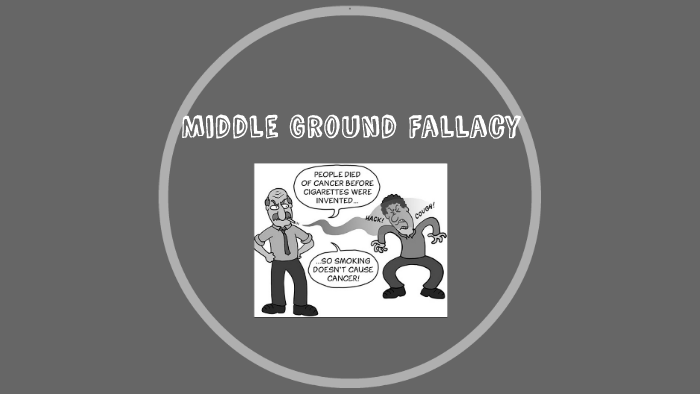

Understanding the Middle Ground Fallacy

The Middle Ground Fallacy, also known as the fallacy of moderation, occurs when individuals or groups assume that the middle point between two extreme positions must be the most reasonable or accurate stance. It suggests that the truth is always a compromise between extremes, disregarding the possibility that one extreme may be closer to reality than the other. This fallacy can lead to suboptimal decisions and the dilution of critical ideas.

Relevance in Decision-Making Processes

The Middle Ground Fallacy is relevant in decision making as it influences how we perceive and evaluate options. It often arises when faced with complex and polarizing issues, as finding a middle ground may appear to be a reasonable and fair approach. However, this fallacy can limit our ability to critically analyze arguments and overlook the importance of examining evidence and considering the merits of each viewpoint independently.

Anchoring in Human Psychology

The Middle Ground Fallacy is anchored in human psychology, specifically in our desire for harmony, compromise, and avoiding conflict. We tend to believe that finding a middle ground promotes fairness and inclusivity. Additionally, our brains often seek cognitive shortcuts, and the middle ground can serve as a mental shortcut to resolve cognitive dissonance or reduce ambiguity. These psychological factors contribute to the prevalence of the Middle Ground Fallacy in our decision-making processes.

Examples of the Middle Ground Fallacy

- Personal Life Decisions: Imagine a couple in a disagreement about where to go on vacation. One partner wants an adventurous backpacking trip, while the other prefers a relaxing beach holiday. Instead of thoroughly discussing their preferences and weighing the pros and cons of each option, they compromise on a mediocre destination that satisfies neither of them. By assuming the middle ground is the best solution, they miss the opportunity to explore alternative options that might better align with their individual desires.

- Business Scenarios: In a business negotiation, two companies are negotiating a partnership agreement. One company proposes a favorable offer, while the other proposes an unfavorable one. Instead of carefully evaluating the merits and potential benefits of each proposal, the parties settle for a middle ground, assuming it to be the fairest compromise. However, this middle ground may not fully leverage the advantages of either proposal, resulting in missed opportunities and compromised outcomes.

- Public Policy-Making: In public policy debates, politicians often seek a middle ground to address contentious issues. While compromise and collaboration are important in policy-making, blindly pursuing a middle ground without critically evaluating the underlying evidence and potential consequences can lead to watered-down policies that fail to address the root problems effectively.

Mental Biases Contributing to the Middle Ground Fallacy

Several mental biases contribute to the Middle Ground Fallacy and reinforce our inclination to seek compromise:

- Ambiguity Bias: The discomfort of ambiguity drives us to gravitate towards a middle ground to reduce uncertainty and find a semblance of clarity. This bias can lead us to overlook nuanced arguments and complexities, favoring simplicity over accuracy.

- Status Quo Bias: Our preference for the familiar and existing conditions can cause us to default to a middle ground, maintaining the status quo. This bias limits our willingness to consider bold and transformative solutions that may lie outside the middle ground.

- Availability Heuristic: Our tendency to rely on readily available information when making decisions can reinforce the Middle Ground Fallacy. If moderate viewpoints are more commonly heard or easily accessible, we may overestimate their validity and overlook more extreme or nuanced perspectives.

Strategies to Mitigate the Middle Ground Fallacy

- Evaluate Each Position Independently: Take the time to analyze and assess the merits and flaws of each extreme viewpoint or option separately. Avoid assuming that the truth must lie in the middle and critically evaluate the evidence and reasoning behind each perspective.

- Seek Objective Information: Engage in extensive research, gather data, and seek diverse sources of information. Expand your understanding of the issue and challenge your preconceived notions. Be wary of confirmation bias and actively seek out evidence that contradicts your initial assumptions.

- Consider Nuanced Solutions: Instead of focusing solely on finding a middle ground, explore alternative solutions that address the underlying concerns of each extreme viewpoint. Look for innovative approaches that incorporate elements from different perspectives while addressing the core issues.

- Embrace Constructive Disagreement: Encourage open dialogue and constructive debate among decision-making groups. Foster an environment where diverse opinions are welcomed, and conflicting viewpoints are thoroughly examined. By challenging assumptions and engaging in thoughtful discussions, a more comprehensive and informed decision-making process can unfold.

Conclusion

The Middle Ground Fallacy presents a significant challenge in decision making, as it leads us to believe that compromise automatically yields the best outcomes. By understanding the fallacy and being aware of the psychological biases that contribute to it, we can approach decision making with greater clarity and objectivity. By evaluating each position independently, seeking objective information, considering nuanced solutions, and fostering constructive disagreement, we can mitigate the Middle Ground Fallacy and make more informed and effective decisions. Ultimately, awareness and active avoidance of this mental trap are crucial for achieving optimal outcomes in personal, business, and public policy contexts.